Curious about what kinds of personal and even private data you may be exposing through the course of a normal day on the internet? How about using “all kinds” as a starting point?

Here, adapted from my new book, Keeping Up: Backgrounders to all the big technology trends you can’t afford to ignore, is a way to break down the scope and nature of the problem by platform.

Financial transactions

Take a moment to visualize what’s involved in a simple online credit card purchase. You probably signed into the merchant’s website using your email address as an account identifier and a (hopefully) unique password. After browsing a few pages, you’ll add one or more more items to the site’s virtual shopping cart.

When you’ve got everything you need, you’ll begin the checkout process, entering shipping information, including a street address and your phone number. You might also enter the account number of the loyalty card the merchant sent you and a coupon code you received in an email marketing message.

Of course, the key step involves entering your payment information. For a credit card, this will probably include the card owner’s name and address, and the card’s number, expiration date, and a security code.

Assuming the merchant’s infrastructure is compliant with Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI-DSS) protocols for handling financial information, then it’s relatively unlikely that this information will be stolen and sold by criminals. But either way, it will still exist within the merchant’s own database.

To flesh all this out a bit, understand that using your loyalty card account and coupon code can communicate a lot of information about your shopping and lifestyle preferences. Not to mention records of some of your previous activities. And your site account comes with contact information and your home location.

All of that information can, at least in theory, be stitched together to create a robust profile of you as a consumer and citizen.

It’s for these reasons that I personally prefer using third-party e-commerce payment systems like PayPal because such transactions leave no record of my specific payment method on the merchant’s own databases.

Devices

Modern operating systems are built from the ground up to connect to the internet in multiple ways. They’ll often automatically query online software repositories for patches and updates and “ask” for remote help when something goes wrong.

Some performance diagnostics data is sent and stored online, where it can contribute to statistical analysis or bug diagnosis and fixes. Individual software packages might connect to remote servers independently of the OS to get their own things done.

All that’s fine. Except that you might have a hard time being sure whether all the data coming and going between your device and the internet is stuff you’re OK sharing.

Can you know that private files and personal information aren’t being swept in with all the other data? And are you confident that none of your data will ever accidentally find its way into some unexpected application lying beyond your control?

To illustrate the problem, I’d refer you to devices powered by digital assistants like Amazon’s Alexa and the Google Assistant (“OK Google”). Since, by definition, the microphones used by digital assistants are constantly listening for their key word (“Alexa…”), everything anyone says within range of the device is registered.

At least some of those conversations are also recorded and stored online and, as it turns out, some of those have eventually been heard by human beings working for the vendor. In at least one case, an inadvertently-recorded conversation was used to convict a murder suspect (not that we’re opposed to convicting murderers).

Amazon, Google, and other players in this space are aware of the issue and are trying to address it. But it’s unlikely they’ll ever fully solve it. Remember, convenience, security, and privacy don’t work well together.

Now if you think the information from computers and tablets that can be tracked and recorded is creepy, wait ’till you hear about thermostats and light bulbs.

As more and more household appliances and tools are adopted as part of “smart home” systems, more and more streams of performance data will be generated alongside them.

And, as has already been demonstrated in multiple real-world applications, all that data can be programmatically interpreted to reveal significant information about what’s going on in a home and who’s doing it.

Mobile devices

Have you ever stopped in the middle of a journey, pulled out your smartphone, and checked a digital map for directions? Of course you have.

Well, the map application is using your current location information and sending you valuable information but, at the same time, you’re sending some equally valuable information back. What kind of information might that be?

I once read about a mischievous fellow in Germany who borrowed a few dozen smartphones, loaded them up on a kids’ wagon, and slowly pulled the wagon down the middle of an empty city street. It wasn’t long before Google Maps was reporting a serious traffic jam where there wasn’t one.

How does the Google Maps app know more about your local traffic conditions than you do? One important class of data that feeds their system is obtained through constant monitoring of the location, velocity, and direction of movement of every active Android phone they can reach – including your Android phone.

I, for one, appreciate this service and I don’t much mind the way my data is used. But I’m also aware that, one day, that data might be used in ways that sharply conflict with my interests. Call it a calculated risk.

Of course, it’s not just GPS-based movement information that Google and Apple – the creators of the two most popular mobile operating systems – are getting. They, along with a few other industry players, are also handling the records of all of our search engine activity and the data returned by exercise and health monitoring applications.

In other words, should they decide to, many tech companies could effortlessly compile profiles describing our precise movements, plans, and health status. And from there, it’s not a huge leap to imagine the owners of such data predicting what we’re likely to do in the coming weeks and months.

Web browsers

Most of us use web browsers for our daily interactions with the internet. And, all things considered, web browsers are pretty miraculous creations. They often act as an impossibly powerful concierge, bringing us all the riches of humanity without even breaking into a sweat.

But, as I’m sure you can already anticipate, all that power comes with a trade-off.

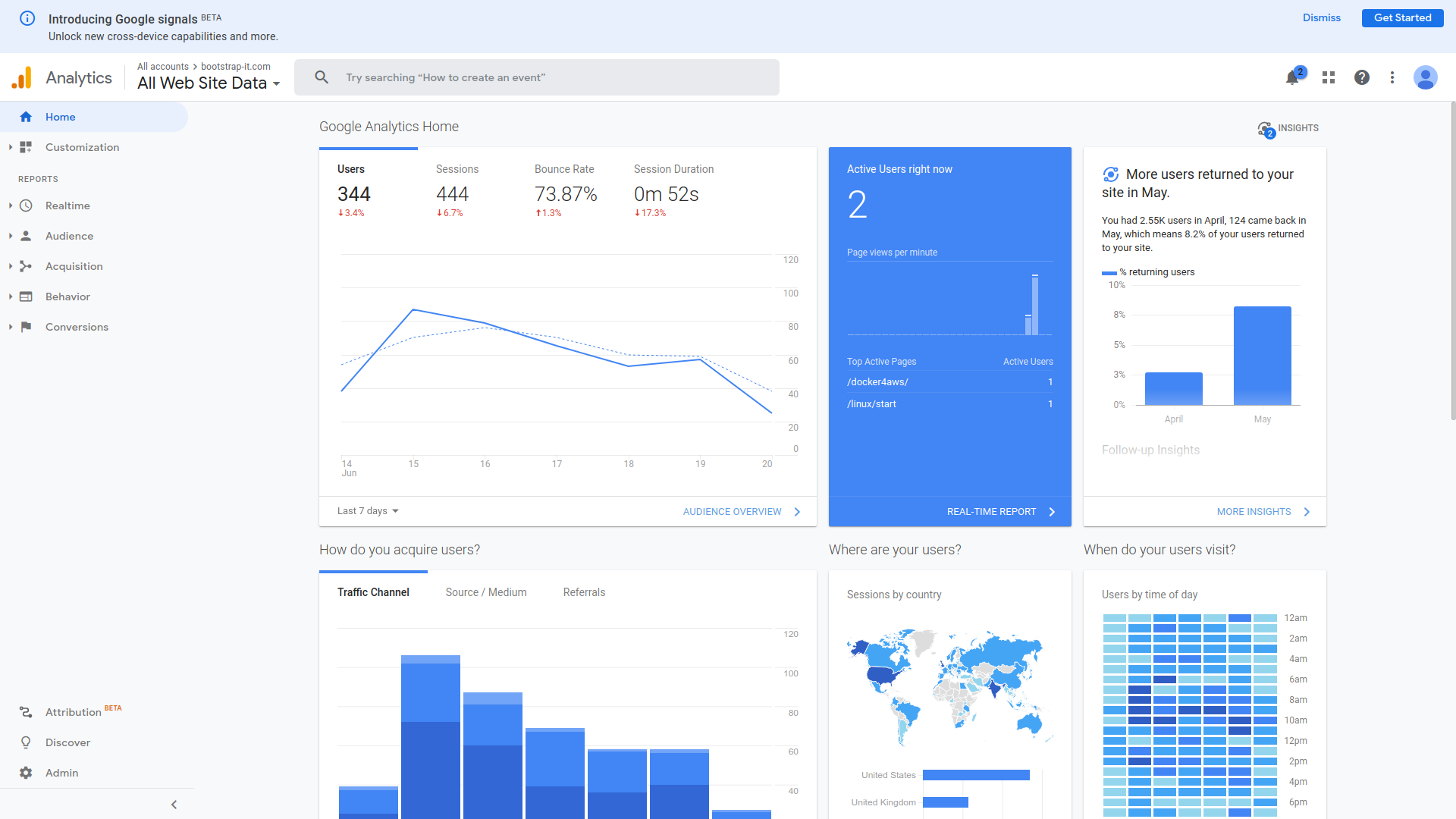

For just a taste of the information your browser freely shares about you, take a look at the Google Analytics page shown in the figure below.

This dashboard displays a visual summary describing all the visits to my own bootstrap-it.com site over the previous seven days. From the data that was collected, I can see:

- Where in the world my visitors are from

- When during the day they tend to visit

- How long they spent on my site

- Which pages they visit

- Which site they left before coming to my site

- How many visitors make repeat visits

- What operating systems they’re running

- What device form factor they’re using (i.e., desktop, smartphone, or tablet)

- The demographic cohorts they belong to (genders, age groups, income groups)

Besides all that, a web server’s own logs can report detailed information, in particular the specific IP address and precise time associated with each visitor.

What this means is that, whenever your browser connects to my website (or any other website), it’s giving my web server an awful lot of information. Google just collects it and presents it to me in a fancy, easy-to-digest format.

By the way, I’m fully aware that, by having Google collect all this information about my website’s users I’m part of the problem. And, for the record, I do feel a bit guilty about it.

In addition, web servers are able to “watch” what you’re doing in real time and “remember” what you did on your last visit.

To explain, have you ever noticed how on some sites, right before you click to leave the page a “Wait! Before you go!” message pops up? Servers can track your mouse movements and, when they get “too close” to closing the tab or moving to a different tab, they’ll display that popup.

Similarly, many sites save small packets of data on your computer called “cookies.” Such a cookie could contain session information that might include the previous contents of a shopping cart or even your authentication status. The goal is to provide a convenient and consistent experience across multiple visits. But such tools can be misused.

Finally, like operating systems, browsers will also silently communicate with the vendor that provides them. Getting usage feedback can help providers stay up to date on security and performance problems. But independent tests have shown that, in many cases, far more data is heading back “home” than would seem appropriate.

Website interaction

Although I deal with this in greater depth in my “Keeping Up” book, I should highlight at least a couple of particularly relevant issues here. Like, for instance, the fact that websites love getting you to sign up for extra value services.

The newsletters and product updates that they’ll send you might we be perfectly legitimate and, indeed, provide great value. But they’re still coming in exchange for some of your private contact information. As long as you’re aware of that, I’ve done my job.

A perfect example is the data you contribute to social media platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn. You may think you’re just communicating with your connections and followers, but it actually goes much further than that.

Take a marvelous – and scary – piece of software called Recon-ng that’s used by network security professionals to test for an organization’s digital vulnerability. Once you’ve configured it with some basics about your organization, Recon-ng will head out to the internet and search for any publicly available information that could be used to penetrate your defenses or cause you harm.

For instance, are you sure outsiders can’t possibly know enough about the software environment your developers work with to do you any damage? Well perhaps you should take a look at the “desired qualifications” section from some of those job ads you posted on LinkedIn. Or how about questions (or answers) your developers might have posted to the Stack Overflow site?

Every post tells a story, and there’s no shortage of clever people out there who love reading stories.

Software like Recon-ng can help you identify potential threats. But that only underlines your responsibility to avoid leaving your data out there in public in the first place.

The bottom line? Smile. You’re being watched.

There’s lots more quick, fun, and accessible technology background goodness available in my Keeping Up book. Take a look.